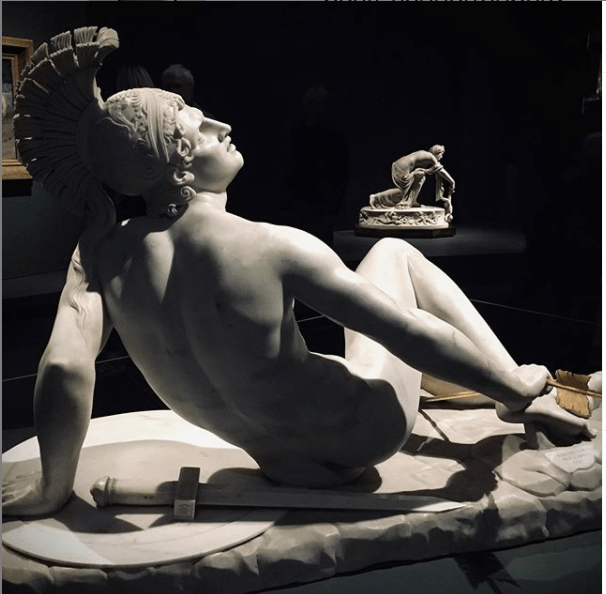

The Oxford Dictionary defines the term ‘Achilles’ Heel’ as a ‘weak point or fault in a person’s character which can be attacked by other people’. It’s important to note though, that the insidious thing about Achilles’ heels is that they’re not obvious. Who would have thought that Achilles, western civilisation’s original hero, would be brought down by a single arrow to the ankle? Why didn’t Homer let his main character die in a Game of Thrones style clash with some Trojan juggernaut? To use a modern analogy, imagine John Rambo being fatally shot in the hand in the middle of the movie right when things are getting interesting.

Protecting our ankles

Given the hidden nature and fatal vulnerability of Achilles’ heels, you might be forgiven for thinking that people try very hard to find and eliminate their personal Achilles’ heels. If we were being perfectly rational about this, you’d be right. After all, being aware of one’s vulnerability is bothersome and disconcerting, right? Unfortunately, people aren’t that straightforward. There seem to be two ways of dealing with vulnerability. First, you can try to eliminate it by taking a hard look at it and confronting it head on. That is the most effective way of dealing with vulnerability, but not necessarily the most popular. The second way people go about eliminating vulnerability, is by simply ignoring it. Looking your own vulnerability squarely in the eyes and dealing with it requires both courage and effort, and it’s in no way easy. By contrast, closing your eyes to one of your weaknesses seems like the easy way out. Out of sight, out of mind, right? Maybe, but unfortunately, out of mind doesn’t equal out of reality. Our unhealthy habits have real world consequences that become increasingly difficult to ignore. At some point they usually find a way of forcing themselves into our awareness. An infected toe can turn gangrenous and end up poisoning the entire body. The harm we have let happen has then become too difficult to ignore.

The point is that looking for one’s Achilles’ heels is scary, and dealing with them can be even scarier. It is nevertheless important to be brave since otherwise one risks harm to what one values, whether that be one’s family, friends or community. While large organisations are different from individual people in some ways, they have a lot of traits in common, and Achilles’ heels are one of them. It therefore is just as important to be aware of the vulnerabilities of one’s community as it is to know one’s own weak spots. As a community of states and citizens, the European Union and the values it’s founded on are of massive value to all of us. We therefore need to ask ourselves how to protect the Europe that we love. We need to find its Achilles’ heel.

Fake Achilles’ heels

When you ask people these days about what they think constitutes the greatest danger to Europe, you will likely get answers like ‘Terrorism’, ‘Populism’ or ‘Pizza Hawaii’. These threats however are like the Trojan juggernauts of old. They’re highly visible, and therefore defeasible. We tackle what we see, and the first step of successfully dealing with a threat is actually seeing it. In Western Europe we’ve long become used to a narrative that tells us that we are immune to certain threats and should better focus on others. For example, we consider that sovereignty over our borders is important. We wouldn’t like for someone to just arbitrarily redraw them. They have, however, not been invaded since WW2 because we’ve all become best friends. Like long-time friends we’ve told each other that “mi casa es tu casa”. European nations used to live each in their own castles. They have now become best friends and flatmates. Like 21st century people never think of catching the black plague, so modern Europeans never even think about threats to their borders. They’re one big happy family. Some of them are stronger than others, but as best friends, they’re all equal in a way. To find what’s most dangerous to Europe today, we need to better understand what Europe today really is. Let’s explore what exactly it means for Europeans to have become best friends and flatmates.

European F.R.I.E.N.D.S

Europe today is more than just a massive common market. Most Europeans today feel like there is an ‘us’, a true common identity that unites them around common values and a shared civilisation. This feeling has for decades now been reinforced by rhetoric on the part of European Institutions and national governments alike. A sense of European identity is what makes our debates extend beyond mere calculations of financial cost and profit. When millions of Ukrainians protested on Kiev’s Maidan Square they weren’t risking their lives to reduce their budget deficit. They were inspired by an idea. What inspires Europeans outside the Union to join and those inside to cooperate is the idea of Europe. As an idea, Europe is a family. Without it, it’s just an economic area. It’s the difference between a friendship and the relationship between you and your coffee shop of choice. If the price or the quality of the coffee changes, you will just go find another source of coffee. Friends, in contrast, you remain loyal to even if, and especially if, they take a turn for the worse. Where there is no common identity, there is no solidarity. Where there is no common identity, each one is ultimately on his own. That, we cannot afford in our private lives, and we cannot afford it in Europe either. Since we cannot afford losing our European friendship, we need to understand its vulnerabilities.

If a friend behaves to you as if you’re just there to benefit him you’ll understand that he’s not really your friend. As friends, you’re precisely not looking to personally profit from your relationship. You’re looking to help each other out, because ultimately there’s a strong “us” between you. Imagine asking your best friend to help you out with some trouble you’re in. If he refuses to talk to you until you’re once again fun to be around, you will rightly consider him to have betrayed your friendship. It doesn’t matter at all who is weaker at any point in time- friends stick to each other or they aren’t friends. The Achilles’ heel of a friendship seems to therefore be this kind of egoistic behaviour. When the “I” takes over, the “us” falls apart. The same holds true on the level of states. If, like the member states belonging to the European Union, you claim to stick together because of common values and a shared identity beyond mere personal profit, then the kind of power politics you’d expect between simple trading partners are out of question. Instead of adhering to the creed of “Country X First” and bullying everyone else into submission, the more powerful states will be guided by what’s best for the whole. Every time states use their power in an egoistic way they undermine their friendship. Like the friendship between simple humans, the European friendship binding together states is not immortal. In fact, since the mere appearance of egoistic behaviour is enough to undermine it, actual bullying is sheer recklessness. Unfortunately, there have been too many instances of both actual and apparent self-centredness in recent years.

Shooting oneself in the heel

One example of a recent episode that triggered what seems like an epidemic of recklessness was the Eurozone Crisis. Year after year politicians from the relatively stable north of Europe and those from the hard-hit south appeared to like nothing so much as to accuse each other of being incompetent, unreliable and egoistic. These Greeks are living off of our money, and they’re not even ashamed of it! Why can’t these German robots think like human beings for once? Instead of explaining to the citizens that they’re ultimately sitting in the same boat with their European neighbours, the loudest voices seemed hellbent on pitting one friend against the other. The cynicism this form of debate has fuelled especially among those who lost out economically is reflected in heightened mistrust towards their supposed friends. That’s pretty unsurprising, considering that each of us distrusts clients and customers more than his best friends. So far, the European friends have not yet degenerated into simple trading partners, but each conflict that turns toxic is one step in the wrong direction. The Eurozone crisis of the 2010’s, while it impacted the lives of millions of people, was merely economic. Nevertheless, the damage that resulted from the toxic debate surrounding it was substantial. Now imagine the impact a more existential threat could have if Europe’s response to it wasn’t united. We are witnessing this exact crisis unfolding right now. Even worse, it affects some of the states that had suffered most under the previous crisis, too.

Far away from the centres of power in Northern Europe, a conflict has been simmering for decades and is slowly reaching its boiling point. Talk to a Western European about threats to territorial sovereignty and he’ll most likely think about black and white news-reels or movies directed by Quentin Tarantino and featuring George Clooney and Brad Pitt. To Europeans living on the south-eastern border of Europe however, threats to their states’ territory have become a feature of everyday life. Greeks and Cypriots have for decades now been the victims of near daily violations of their borders by their larger neighbour Turkey. How come, you might wonder, that Greece and Cyprus’ powerful European friends haven’t united to deal with this threat long ago? The truth is, that until fairly recently it was simply easier to ignore the literally tens of thousands of violations of Greek airspace and the literally tens of thousands Turkish troops occupying the northern half of the Republic of Cyprus. Why? Well, Turkey was like a rich kid that sometimes brings some cool stuff to school and that can be fun to play with, but that also has some skeletons in its closet. They’re pretty bad, but you’d rather not spoil the fun as long as things don’t get out of hand. In particular, you’re worried that if you mention the skeletons, the rich kid will join the rival gang in the schoolyard, upgrading their collection of gadgets and inviting them to its parties. The point is, however, that things have long since gotten out of hand. The skeletons in Turkey’s closet are European, and by ignoring them the European friends have slowly but steadily been undermining themselves.

The European Achilles

As you might have guessed by this point, I am arguing that Europe’s Achilles’ heel lies in its South Eastern flank. It has remained unprotected for long enough that those who don’t care too much about Europe have been able to use it for leisurely target practice. If Europe doesn’t wake up to this threat now, it risks a being hit fatally. The threat is not military defeat, for the immediate military threat does not extend beyond Greece and Cyprus. What risks bringing down the whole of the European Achilles is rather the lack of loyalty among its constituent parts. If the more powerful, but less directly impacted states of Europe look away while their supposed best friends are under assault, they are in fact complicit themselves. Just like the attacker, they are putting the slogan “Country X First” into practice, thereby further eroding the bonds of friendship holding together the European Achilles. Only this time the risk is very high that the damage they’re inflicting on him will be irreversible. The Turkish navy has for years now been intruding into Cypriot waters, and now appears poised to extend its “exploratory operations” to those of Greece. Unlike Cyprus, Greece does have a substantial navy of its own, and its President can hardly afford to let a hostile power run roughshod over its territory. In 1996, when the conflict very nearly turned hot, it was defused at the last second by President Clinton. Since then, the Turkish Airforce has continued to violate Greek airspace on a daily basis, while Turkey claims ever larger chunks of the Aegean for itself and seems more willing than ever to engage in brinkmanship. To grasp the extent of the Turkish government’s recklessness here, please note the current effort by of President Erdogan to turn the Hagia Sophia into a mosque. By pledging to add one more mosque to a city that already boasts over 3500 of them at a time of global instability, and having himself used relations with Europe, Greece and Cyprus as a PR tool, he now appears willing to sacrifice even the last pretence of good faith. Don’t be fooled. All this is not just a threat to Greeks and Cypriots. Europe’s response will send a message to all who live by the law of the jungle. It would be a fatal mistake to believe that appeasement will work today any more than it did in the 1930’s. One’s heel looks like it’s far away from one’s eyes, but only as long as one can reliably stand on it.

In the absence of a fundamental policy shift in Ankara, it is only a question of time until the conflict boils over. If the states of Europe remember their professed common values, they’ll stand together now, deterring further escalation before it is too late. They need to realise now, that disunity will ultimately benefit none of them. Instead, those of them that feel betrayed will turn towards other, perhaps more protective allies and give up on the European idea. By betraying their friendship, the greater powers will have betrayed themselves. By harming their less powerful friends, they will have harmed themselves. A future in which a disunited Europe faces a world in which might makes right is not one in which any European state stands a good chance of succeeding. However, it will be one that Europeans brought onto themselves. It is not too late, but the clock is ticking.